Arabian Nights in Baraza

20th September 2018

Songs, stories and the spirit of the past at the Zanzibar Collection

Words by Carolyn Burdet

Three tall Maasai tribesmen, dressed in cotton robes of orange the colour of flaming sunsets, stand perfectly poised on the shoreline, a silhouette against the white sand. We are in Africa, this is the Indian Ocean. The sea is clear as aquamarine crystal, the wide horizon curved as a watermelon. If you aimed your telescope from atop a ship’s mast to steer the galleon out into the Indian Ocean, you’d have the Maldives in sight, dots of sandy beach. Little sailing boats lilting in the sand give no hint of a turbulent past, of shipwrecked sultans and slave ships heaving with the misery of human cargo. From the moment the pilot on Kenya Airways greeted us with ‘Jambo’ we are in the heart of Africa. We breakfast in the creative hub of Nairobi, and by sunrise the plane is circling the crater at the peak of Mount Kilimanjaro, rising high above the clouds, before we land in Zanzibar, an archipelago of islands off the east coast of Tanzania in Africa, a paradise on the silk trading and spice route in the Indian Ocean. Now we are staring out at the Indian Ocean, as Maasai tribesmen disappear from view. Many tourists arrive in Zanzibar footsore from trekking Mount Kilimanjaro, the tallest mountain in Africa, for a restoration week by the beach… or dusty from a game drive safari on mainland Tanzania, Kenya or Zimbabwe. There is no big game on Zanzibar; the big five here are zebra fish, parrot fish, butterfly fish, striped Moorish fish, and trumpet fish, darting in and out of the coral reef. This is an ocean playground of diving and snorkeling. Dolphins dance off the southern coast of Zanzibar, and whales migrate in the ocean’s depths off the east coast. A path of wooden slats stretches towards the sea as we step across shallow rockpools to a boat waiting to take us to Mswakini lagoon. The only people in sight are oyster-catchers on the sandbanks at low tide. Wading thigh deep, hoiking our shirts above the waves, we climb aboard the creaky wooden boat, and the skipper hauls a rusting anchor onto the deck. We head out to the sparkling turquoise lagoon. Swimming from the boat across the currents to the coral reef, our diving instructor Hassan sings through his snorkel. Bubbles rise from oxygen tanks as divers surface, gasping in wonder at hearing whale song under the sea. Back at Paje, a five-mile stretch of fine sand, Breezes is a lighthearted, barefoot resort, one of the hotels in the Zanzibar Collection. Kayaks and kite surfboards are propped up against palm trees on the beach outside the watersports centre, and a blackboard boasts tropical fish seen on today’s snorkelling trip on the reef.  Baraza reception A lunch for castaways is set up on the deserted beach at The Palms, under a makeshift gazebo of bamboo sticks with billowing white drapes. Silver service on the sand, white linen tablecloth, ice buckets, menus on banana leaves, napkin rings in the shape of giraffe and zebra carved by Maasai in striped zebrawood nodding to the safari connection on mainland Tanzania. This is the closest it comes to paradise. Next day the Indian Ocean beckons with brightness. We take an early morning reef walk at low tide, collecting shells on the sandy beach at Bwejuu Paje, a stretch of powder fine white sand listed as one of the most glorious beaches in the world. A few fishermen are tending their dhows, traditional sailing boats, sea-beaten and flaking as they lilt on the sand. An elderly woman from Bwejuu village is burying coconut husks in the sand at the water’s edge, her head wrapped in a scarf under the blazing equatorial sunshine. Coconut fibres are seasoned in the sand, then used for ropes and building materials for village houses, made with mud brick walls, palm leaf roofs and picket fences around the outdoor kitchen where families cook bean stew and rice with coconut milk over an open fire. In Bwejuu, village life has been untouched since the 11th century, a simple subsistence lifestyle based on coconuts, spices, fishing and a well for clean drinking water. Giggling children follow us from the village, shyly sharing currency of seashells as a token of friendship, hugging the books we gift in exchange. Everywhere we go, children peep round from trees and ask, hopefully, “Book?”. Vanilla and cocoa are grown in this luscious island, the theobroma trees laden with heavy pods. The spice forest yields glamorous secrets: nutmeg and glossy red mace grow within cases like jewellery boxes, ylang ylang is prized by parfumiers, and lipstick fruit is named after the juicy scarlet pips worn as make up.

Baraza reception A lunch for castaways is set up on the deserted beach at The Palms, under a makeshift gazebo of bamboo sticks with billowing white drapes. Silver service on the sand, white linen tablecloth, ice buckets, menus on banana leaves, napkin rings in the shape of giraffe and zebra carved by Maasai in striped zebrawood nodding to the safari connection on mainland Tanzania. This is the closest it comes to paradise. Next day the Indian Ocean beckons with brightness. We take an early morning reef walk at low tide, collecting shells on the sandy beach at Bwejuu Paje, a stretch of powder fine white sand listed as one of the most glorious beaches in the world. A few fishermen are tending their dhows, traditional sailing boats, sea-beaten and flaking as they lilt on the sand. An elderly woman from Bwejuu village is burying coconut husks in the sand at the water’s edge, her head wrapped in a scarf under the blazing equatorial sunshine. Coconut fibres are seasoned in the sand, then used for ropes and building materials for village houses, made with mud brick walls, palm leaf roofs and picket fences around the outdoor kitchen where families cook bean stew and rice with coconut milk over an open fire. In Bwejuu, village life has been untouched since the 11th century, a simple subsistence lifestyle based on coconuts, spices, fishing and a well for clean drinking water. Giggling children follow us from the village, shyly sharing currency of seashells as a token of friendship, hugging the books we gift in exchange. Everywhere we go, children peep round from trees and ask, hopefully, “Book?”. Vanilla and cocoa are grown in this luscious island, the theobroma trees laden with heavy pods. The spice forest yields glamorous secrets: nutmeg and glossy red mace grow within cases like jewellery boxes, ylang ylang is prized by parfumiers, and lipstick fruit is named after the juicy scarlet pips worn as make up.  Fisherman with dhow We visit the community spice farm on Unguja island, where cinnamon trees are stripped of their spicy bark for medicinal use for fevers, headache and stomach cramps. The villagers in Kizimbani village grow cardamom, vanilla, fruits and cloves in the spice forest. Boys shin up coconut trees for fresh coconuts, and children run around playing like the tiny quail chicks scuttling to and fro in the pineapple patch. Music is playing, families are singing, women in colourful printed robes are stirring spices into the communal cooking pots over a smoky open-air fire, as a boy weaves baskets of palm plaited with jasmine flowers. Jozani forest of eucalyptus, redwood and mahogany trees at the heart of the island is home to indigenous Red Colobus monkeys, blue monkeys with their characteristic Mohican, and brightly colourful birds, like the golden tinkerbird. The northern tip of Zanzibar has saltwater mangrove swamps where lobster-red crabs poke a claw among the gnarled tangle of tree roots.

Fisherman with dhow We visit the community spice farm on Unguja island, where cinnamon trees are stripped of their spicy bark for medicinal use for fevers, headache and stomach cramps. The villagers in Kizimbani village grow cardamom, vanilla, fruits and cloves in the spice forest. Boys shin up coconut trees for fresh coconuts, and children run around playing like the tiny quail chicks scuttling to and fro in the pineapple patch. Music is playing, families are singing, women in colourful printed robes are stirring spices into the communal cooking pots over a smoky open-air fire, as a boy weaves baskets of palm plaited with jasmine flowers. Jozani forest of eucalyptus, redwood and mahogany trees at the heart of the island is home to indigenous Red Colobus monkeys, blue monkeys with their characteristic Mohican, and brightly colourful birds, like the golden tinkerbird. The northern tip of Zanzibar has saltwater mangrove swamps where lobster-red crabs poke a claw among the gnarled tangle of tree roots.  Child behind tree, spice forest Back at the Baraza hotel a campfire is blazing in a fire pit on the beach. Three luxury boutique hotels in the Zanzibar Collection sit along this stretch of beach, set in lush tropical gardens of soft pink bougainvillea fluttering like butterfly wings, poppy red hibiscus flowers furling like parasols in the midday sun, and umbrella shade from tall trees that drop wooden seed pods shaped like canapé dishes. Breezes and Palms are built in the style of safari lodges with traditional thatched roofs. The Safari bar is in a vast open-sided yurt under a thatched roof. Breezes bar is a safari tent built around a vast Mvinje tree trunk, a giant conifer from the island’s forest. It is drenched in references to Zanzibar’s place on the spice and silk routes, purple and gold silk cushions and glass topped spice racks as tables. Breezes was the first hotel in the Zanzibar Collection, opened 20 years ago with the first spa on the island. Families are welcome here; the swimming pool is a lozenge close to The Breakers beach barbecue grill, where you can throw on a sarong and eat fresh seafood, red snapper or surf and turf with your feet on the white sand. A beachfront dining pavilion is booked for weddings and lantern-lit private dinner parties, where guests can enjoy the view without being seen.

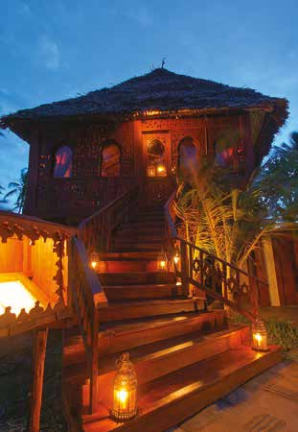

Child behind tree, spice forest Back at the Baraza hotel a campfire is blazing in a fire pit on the beach. Three luxury boutique hotels in the Zanzibar Collection sit along this stretch of beach, set in lush tropical gardens of soft pink bougainvillea fluttering like butterfly wings, poppy red hibiscus flowers furling like parasols in the midday sun, and umbrella shade from tall trees that drop wooden seed pods shaped like canapé dishes. Breezes and Palms are built in the style of safari lodges with traditional thatched roofs. The Safari bar is in a vast open-sided yurt under a thatched roof. Breezes bar is a safari tent built around a vast Mvinje tree trunk, a giant conifer from the island’s forest. It is drenched in references to Zanzibar’s place on the spice and silk routes, purple and gold silk cushions and glass topped spice racks as tables. Breezes was the first hotel in the Zanzibar Collection, opened 20 years ago with the first spa on the island. Families are welcome here; the swimming pool is a lozenge close to The Breakers beach barbecue grill, where you can throw on a sarong and eat fresh seafood, red snapper or surf and turf with your feet on the white sand. A beachfront dining pavilion is booked for weddings and lantern-lit private dinner parties, where guests can enjoy the view without being seen.  Beachfront dining The villas at Zawadi, meaning ‘gift’ in Swahili, on the headland along this pristine coastline, attracts honeymoon couples. Villas dotted around the garden are built like a modern kitchen extension, an open plan living room with sliding glass window walls to a terrace, each with a plunge pool and ocean views. The contemporary palette of bleached driftwood, chalky white and dolphin grey, and walk-through power showers, gives no hint of the history of time or place. The Palms from the Zanzibar Collection could be on a desert island. Less flip flops, more Gucci loafers, it’s so exclusive it has only six palm-thatched suites, each with a private cabana on the beach and a tub on the shaded deck, and guests meet for sundowners in the vast bar with colonial style teak floors.

Beachfront dining The villas at Zawadi, meaning ‘gift’ in Swahili, on the headland along this pristine coastline, attracts honeymoon couples. Villas dotted around the garden are built like a modern kitchen extension, an open plan living room with sliding glass window walls to a terrace, each with a plunge pool and ocean views. The contemporary palette of bleached driftwood, chalky white and dolphin grey, and walk-through power showers, gives no hint of the history of time or place. The Palms from the Zanzibar Collection could be on a desert island. Less flip flops, more Gucci loafers, it’s so exclusive it has only six palm-thatched suites, each with a private cabana on the beach and a tub on the shaded deck, and guests meet for sundowners in the vast bar with colonial style teak floors.  The Palms bath On the other side of the huge arched wooden doorway in the gardens is Baraza hotel, built on the dreams of an Arabian palace. The Raguž family, who own The Zanzibar Collection, had run safari holidays in Kenya. When they came to Zanzibar, they fell under the spell of the Indian Ocean and its long stretch of white sand. There was nothing but coast, forest and the village. They built the infrastructure of roads from Stone Town, brought electricity and piped water supply to the village of Bwejuu, and to their hotels, bringing the neo-colonialisation of the tourist trade. Mrs Raguž’s daughter Nathalie, an interior designer based in Nairobi, designed the architecture and interiors of Baraza with her husband Adriano Fusillo. The décor is a fusion of Arabian opulence with Swahili arches, Indian wood-carved furniture, decorated brass lanterns, antiques and bespoke handmade furniture evocative of languishing on the Sultana’s curtained chaises. Baraza is a calm, cool palace, colonnaded corridors of twinkling mosaic and white minaret cut-out windows in the dazzling white walls. “Arabic interiors are usually very opulent with a lot of colours and patterns and decorative items,” says Nathalie. “We used just one colour in the fabrics, in different textures, and brass lanterns against the cream backdrop, so the beautiful views wouldn’t be overshadowed.” Wandering radial mosaic paths, to get the full maze of the palace into view, it’s hard to shrink the sheer scale into perspective. Estimating the number of minaret archway windows along the corridors is like counting the holes in a Tetley tea bag. Cultural influences carried on the trade winds are celebrated at Baraza, with feasts of African and Zanzibari dishes of cinnamon and coconut scented rice, spicy Persian, Indian and Asian curries and warm, fluffy local Swahili bread.

The Palms bath On the other side of the huge arched wooden doorway in the gardens is Baraza hotel, built on the dreams of an Arabian palace. The Raguž family, who own The Zanzibar Collection, had run safari holidays in Kenya. When they came to Zanzibar, they fell under the spell of the Indian Ocean and its long stretch of white sand. There was nothing but coast, forest and the village. They built the infrastructure of roads from Stone Town, brought electricity and piped water supply to the village of Bwejuu, and to their hotels, bringing the neo-colonialisation of the tourist trade. Mrs Raguž’s daughter Nathalie, an interior designer based in Nairobi, designed the architecture and interiors of Baraza with her husband Adriano Fusillo. The décor is a fusion of Arabian opulence with Swahili arches, Indian wood-carved furniture, decorated brass lanterns, antiques and bespoke handmade furniture evocative of languishing on the Sultana’s curtained chaises. Baraza is a calm, cool palace, colonnaded corridors of twinkling mosaic and white minaret cut-out windows in the dazzling white walls. “Arabic interiors are usually very opulent with a lot of colours and patterns and decorative items,” says Nathalie. “We used just one colour in the fabrics, in different textures, and brass lanterns against the cream backdrop, so the beautiful views wouldn’t be overshadowed.” Wandering radial mosaic paths, to get the full maze of the palace into view, it’s hard to shrink the sheer scale into perspective. Estimating the number of minaret archway windows along the corridors is like counting the holes in a Tetley tea bag. Cultural influences carried on the trade winds are celebrated at Baraza, with feasts of African and Zanzibari dishes of cinnamon and coconut scented rice, spicy Persian, Indian and Asian curries and warm, fluffy local Swahili bread.  Breezes, The Tides Nathalie and her sister design the Palacina range of clothing, wisps of painted chiffon kaftans, silk dresses, and crisp linen menswear shirts, made by their own team of tailors, who sew the fine bed linen and soft furnishings for these boutique hotels. Nathalie wanted to create a magical place that was never over the top. “Zanzibar always had a magical connotation about it. It was important to us that it felt relaxed and understated.” Decorative stucco carving around the doorframes was created by local craftsmen etching patterns into the cement with small knives.

Breezes, The Tides Nathalie and her sister design the Palacina range of clothing, wisps of painted chiffon kaftans, silk dresses, and crisp linen menswear shirts, made by their own team of tailors, who sew the fine bed linen and soft furnishings for these boutique hotels. Nathalie wanted to create a magical place that was never over the top. “Zanzibar always had a magical connotation about it. It was important to us that it felt relaxed and understated.” Decorative stucco carving around the doorframes was created by local craftsmen etching patterns into the cement with small knives.  Baraza pool At Baraza, the concept of indulgently unwinding in luxury stretches before you as wide as the Indian Ocean. Laughter peals around the grounds as gardeners collect coconuts. A lizard basking in the sun darts at the movement of a shadow, a gecko dances on the path. Gharib, an all-knowing courtier in this palace, whispers a few words in Swahili, and a glass of chilled hibiscus juice made from the pressed flowers, arrives carried aloft on a brass tray. Be a recluse in the library, a leather-bound hideaway of bookshelves. Lie by the oceanfront pool as an ice bucket is brought with chilled wine or bottled water to quench the afternoon ardour. Salute the sun at a Hatha yoga class with ever-smiling Sree, a yogi from India. Retire from the heat to the luxuriant spa and recline on the gold curtained throne beds of a Sultan’s harem, sipping ginger tea in a heap of pummelled unfurled tension after a Balinese massage. Baraza spa pool is set within a formal quadrangle courtyard of white quartz gravel. Swimming alone at dusk with the underwater music, a murmuration of swallows swoops over the rooftops as the constellations twinkle in the sky.

Baraza pool At Baraza, the concept of indulgently unwinding in luxury stretches before you as wide as the Indian Ocean. Laughter peals around the grounds as gardeners collect coconuts. A lizard basking in the sun darts at the movement of a shadow, a gecko dances on the path. Gharib, an all-knowing courtier in this palace, whispers a few words in Swahili, and a glass of chilled hibiscus juice made from the pressed flowers, arrives carried aloft on a brass tray. Be a recluse in the library, a leather-bound hideaway of bookshelves. Lie by the oceanfront pool as an ice bucket is brought with chilled wine or bottled water to quench the afternoon ardour. Salute the sun at a Hatha yoga class with ever-smiling Sree, a yogi from India. Retire from the heat to the luxuriant spa and recline on the gold curtained throne beds of a Sultan’s harem, sipping ginger tea in a heap of pummelled unfurled tension after a Balinese massage. Baraza spa pool is set within a formal quadrangle courtyard of white quartz gravel. Swimming alone at dusk with the underwater music, a murmuration of swallows swoops over the rooftops as the constellations twinkle in the sky.  Baraza bathroom Winding along mosaic-tiled cloisters, twinkling in the candlelight cast by rows of brass lanterns, we pause by a fountain in the inner courtyard. “What can we expect of Stone Town tomorrow?” The general manager Jaume’s turn of phrase is as allegorical as Gabriel García Marquez. “So many emotions. She’s like an elderly lady. No longer as beautiful, perhaps, but so many memories in her eyes.”

Baraza bathroom Winding along mosaic-tiled cloisters, twinkling in the candlelight cast by rows of brass lanterns, we pause by a fountain in the inner courtyard. “What can we expect of Stone Town tomorrow?” The general manager Jaume’s turn of phrase is as allegorical as Gabriel García Marquez. “So many emotions. She’s like an elderly lady. No longer as beautiful, perhaps, but so many memories in her eyes.”  Baraza living Stone Town, the capital of Zanzibar, has seen every era of history. The House of Wonders, Beit el-Ajaib, was the first building on Zanzibar to have the miraculous inventions of electricity, tap water, a lift and a telephone. The building stands immense, an imposing Brutalist while hulk carved with inscriptions. Cannons from Portugese gunships line the dock. Portraits of Sultans and Princesses deck the walls of the wood-panelled city museum, an abandoned Sultan’s residence with echoes of the Arabian royalty who lauded over this tiny realm. The Sultan’s bed creaks with exhaustion at the tales of the 99 concubines who bore his sons. An ornate Venetian glass chandelier presiding over the ballroom is incongruous in this deserted palace on the brink of the Indian Ocean. In 1896, the British Navy defended the Sultan when his brother tried to seize the throne, deciding the brother was “somewhat weak in the head”. The shortest war in history lasted 45 minutes and ended the matter. Poetic love letters framed in the museum tell the true story of the whirlwind romance of a princess in exile in Victorian times. The Sultan’s daughter, Princess Salme, scandalously eloped with a German officer, then after being tragically widowed implored her brothers, the Sultans of Zanzibar and Oman, to let her come home. Passing a shady shop doorway in Stone Town, a glimpse of a curved obelisk, a tusk, is testament to the loss of elephant life by poachers for the illegal ivory trade. The island’s elephants were slaughtered by Portugese colonialists, and the last leopard was killed in the belief that they were associated with the magical tradition that was driven out by Arab rule. These are not the only cruel trades of the island’s history. We are guided through centuries of the dark years of harsh rule by Portugese traders, who dealt in ships laden with human cargo, an evil trade in 20,000 slaves a year from Africa and Asia.

Baraza living Stone Town, the capital of Zanzibar, has seen every era of history. The House of Wonders, Beit el-Ajaib, was the first building on Zanzibar to have the miraculous inventions of electricity, tap water, a lift and a telephone. The building stands immense, an imposing Brutalist while hulk carved with inscriptions. Cannons from Portugese gunships line the dock. Portraits of Sultans and Princesses deck the walls of the wood-panelled city museum, an abandoned Sultan’s residence with echoes of the Arabian royalty who lauded over this tiny realm. The Sultan’s bed creaks with exhaustion at the tales of the 99 concubines who bore his sons. An ornate Venetian glass chandelier presiding over the ballroom is incongruous in this deserted palace on the brink of the Indian Ocean. In 1896, the British Navy defended the Sultan when his brother tried to seize the throne, deciding the brother was “somewhat weak in the head”. The shortest war in history lasted 45 minutes and ended the matter. Poetic love letters framed in the museum tell the true story of the whirlwind romance of a princess in exile in Victorian times. The Sultan’s daughter, Princess Salme, scandalously eloped with a German officer, then after being tragically widowed implored her brothers, the Sultans of Zanzibar and Oman, to let her come home. Passing a shady shop doorway in Stone Town, a glimpse of a curved obelisk, a tusk, is testament to the loss of elephant life by poachers for the illegal ivory trade. The island’s elephants were slaughtered by Portugese colonialists, and the last leopard was killed in the belief that they were associated with the magical tradition that was driven out by Arab rule. These are not the only cruel trades of the island’s history. We are guided through centuries of the dark years of harsh rule by Portugese traders, who dealt in ships laden with human cargo, an evil trade in 20,000 slaves a year from Africa and Asia.  Stone Town A museum to commemorate the slave trade is in a square near Christ church. We emerge blinking into bright daylight from the despair of the dungeons. A man outside is singing the hymn Lord of All Hopefulness in Swahili. Another Zanzibari man with a stall of freshly picked bananas outside the church across the square joins the hymn in deep baritone. It’s a song of redemption, unspeakably moving, balm for the sadness. The slave trade eventually ended 100 years after Livingstone’s treaties were signed, upheld by the British Navy patrolling the seas to prevent the Sultan from transporting slaves. The island expelled the Omani colonial rulers in 1964 and became part of Tanzania, a democracy where Swahili is a unifying language for many tribes and cultures. Palaces and embassies lie abandoned. In the crumbling colonial grandeur of Stone Town, a handsomely restored building owned by the Aga Khan stands crisp among the flaking plasterwork of the fading grandeur of surrounding buildings.

Stone Town A museum to commemorate the slave trade is in a square near Christ church. We emerge blinking into bright daylight from the despair of the dungeons. A man outside is singing the hymn Lord of All Hopefulness in Swahili. Another Zanzibari man with a stall of freshly picked bananas outside the church across the square joins the hymn in deep baritone. It’s a song of redemption, unspeakably moving, balm for the sadness. The slave trade eventually ended 100 years after Livingstone’s treaties were signed, upheld by the British Navy patrolling the seas to prevent the Sultan from transporting slaves. The island expelled the Omani colonial rulers in 1964 and became part of Tanzania, a democracy where Swahili is a unifying language for many tribes and cultures. Palaces and embassies lie abandoned. In the crumbling colonial grandeur of Stone Town, a handsomely restored building owned by the Aga Khan stands crisp among the flaking plasterwork of the fading grandeur of surrounding buildings.  Baraza bar Baraza is a dream of how this World Heritage site could be after restoration. We are on the roof terrace of one of the minarets of the hotel. Isaak moves silently in his long gown, pouring a decanter of the island’s local medicinal nectar, cane spirit infused with honey and ginger poured over crushed ice, his voice as mellifluous as the honey in the cocktail. The House of Wonders in Stone Town now stands empty, stripped of its fixtures and fittings when the government offices closed, the artefacts of an era sold off at auction. The writing desk and Bakelite telephone on the wall behind the reception in Breezes are from the House of Wonders. Arabic lanterns and brass kettles, Swahili tradition for welcoming guests, line the shelves; ebony wardrobes decorated with ornamental carving techniques learned from Indian craftsmen are inset with bone.

Baraza bar Baraza is a dream of how this World Heritage site could be after restoration. We are on the roof terrace of one of the minarets of the hotel. Isaak moves silently in his long gown, pouring a decanter of the island’s local medicinal nectar, cane spirit infused with honey and ginger poured over crushed ice, his voice as mellifluous as the honey in the cocktail. The House of Wonders in Stone Town now stands empty, stripped of its fixtures and fittings when the government offices closed, the artefacts of an era sold off at auction. The writing desk and Bakelite telephone on the wall behind the reception in Breezes are from the House of Wonders. Arabic lanterns and brass kettles, Swahili tradition for welcoming guests, line the shelves; ebony wardrobes decorated with ornamental carving techniques learned from Indian craftsmen are inset with bone.  Baraza bedroom At Baraza, the ebony chaises, canopied daybeds and an elongated armchair for adorning the Sultana’s arms with henna, are familiar from the museum. An ancient snaggle-toothed piano looks shipwrecked. It can no longer hold the tune, but it holds the island’s history. Hand-carved wooden chests speak of treasure, buried in the sand centuries ago. It’s rumoured the treasure is still undiscovered. Mr Bindu the village storyteller holds us spellbound. “The African Queen Manu Mwana held sway on the island, until Persia decided to settle as rulers. The Sultan of Oman sent his sons. The brothers set out from Persia, sailing on the Indian Ocean for a long time, when their dhow ran into a storm.” Mr Bindu pauses for us to take in the scene. “One brother was carried north by the ocean currents to the island of Pemba. One brother was swept ashore on the island of Unjuja and started walking, carrying on until he reached Stone Town. One of the Sultan’s sons was captured by pirates off the coast of Africa. “The fourth brother was eaten by a shark. Only his hand remained. It was washed ashore at Stone Town and found by fishermen.” There is a slight gasp, candles flickering at the change of air. It is a warm evening, with a gentlest of breezes from the Indian Ocean. We had been lulled by Mr Bindu’s deep sonorous voice delivering centuries of the island’s history, through African Queens, Persian palaces, local island tribes, and dates of shifts in power from the Ottoman Empire. The story of the pirates is listed in history books, but the shark leaving only a hand could be a tall tale. Later, the moon rises like a smile, gracing the beach bonfire party. Then home to the lap of luxury in the villa with its own plunge pool, its deep copper bath tub the size of a ship, to dream the dreams of Arabian Nights, with muslin drapes swept around the bed. Flights from Heathrow to Zanzibar via Nairobi and Kilimanjaro www.kenya-airways.com www.thezanzibarcollection.com How to help Baraza for Bwejuu is the Zanzibar Collection’s charity in support of the local village. The village kindergarten depends on donations for food. If visiting, donations of books, clinic supplies and simple (non-battery, non-mains) solar lights are greatly appreciated, and the local school is in need of a working laptop. For more information see https://www.baraza-zanzibar.com/giving-back/

Baraza bedroom At Baraza, the ebony chaises, canopied daybeds and an elongated armchair for adorning the Sultana’s arms with henna, are familiar from the museum. An ancient snaggle-toothed piano looks shipwrecked. It can no longer hold the tune, but it holds the island’s history. Hand-carved wooden chests speak of treasure, buried in the sand centuries ago. It’s rumoured the treasure is still undiscovered. Mr Bindu the village storyteller holds us spellbound. “The African Queen Manu Mwana held sway on the island, until Persia decided to settle as rulers. The Sultan of Oman sent his sons. The brothers set out from Persia, sailing on the Indian Ocean for a long time, when their dhow ran into a storm.” Mr Bindu pauses for us to take in the scene. “One brother was carried north by the ocean currents to the island of Pemba. One brother was swept ashore on the island of Unjuja and started walking, carrying on until he reached Stone Town. One of the Sultan’s sons was captured by pirates off the coast of Africa. “The fourth brother was eaten by a shark. Only his hand remained. It was washed ashore at Stone Town and found by fishermen.” There is a slight gasp, candles flickering at the change of air. It is a warm evening, with a gentlest of breezes from the Indian Ocean. We had been lulled by Mr Bindu’s deep sonorous voice delivering centuries of the island’s history, through African Queens, Persian palaces, local island tribes, and dates of shifts in power from the Ottoman Empire. The story of the pirates is listed in history books, but the shark leaving only a hand could be a tall tale. Later, the moon rises like a smile, gracing the beach bonfire party. Then home to the lap of luxury in the villa with its own plunge pool, its deep copper bath tub the size of a ship, to dream the dreams of Arabian Nights, with muslin drapes swept around the bed. Flights from Heathrow to Zanzibar via Nairobi and Kilimanjaro www.kenya-airways.com www.thezanzibarcollection.com How to help Baraza for Bwejuu is the Zanzibar Collection’s charity in support of the local village. The village kindergarten depends on donations for food. If visiting, donations of books, clinic supplies and simple (non-battery, non-mains) solar lights are greatly appreciated, and the local school is in need of a working laptop. For more information see https://www.baraza-zanzibar.com/giving-back/

Call

Call Book Now

Book Now